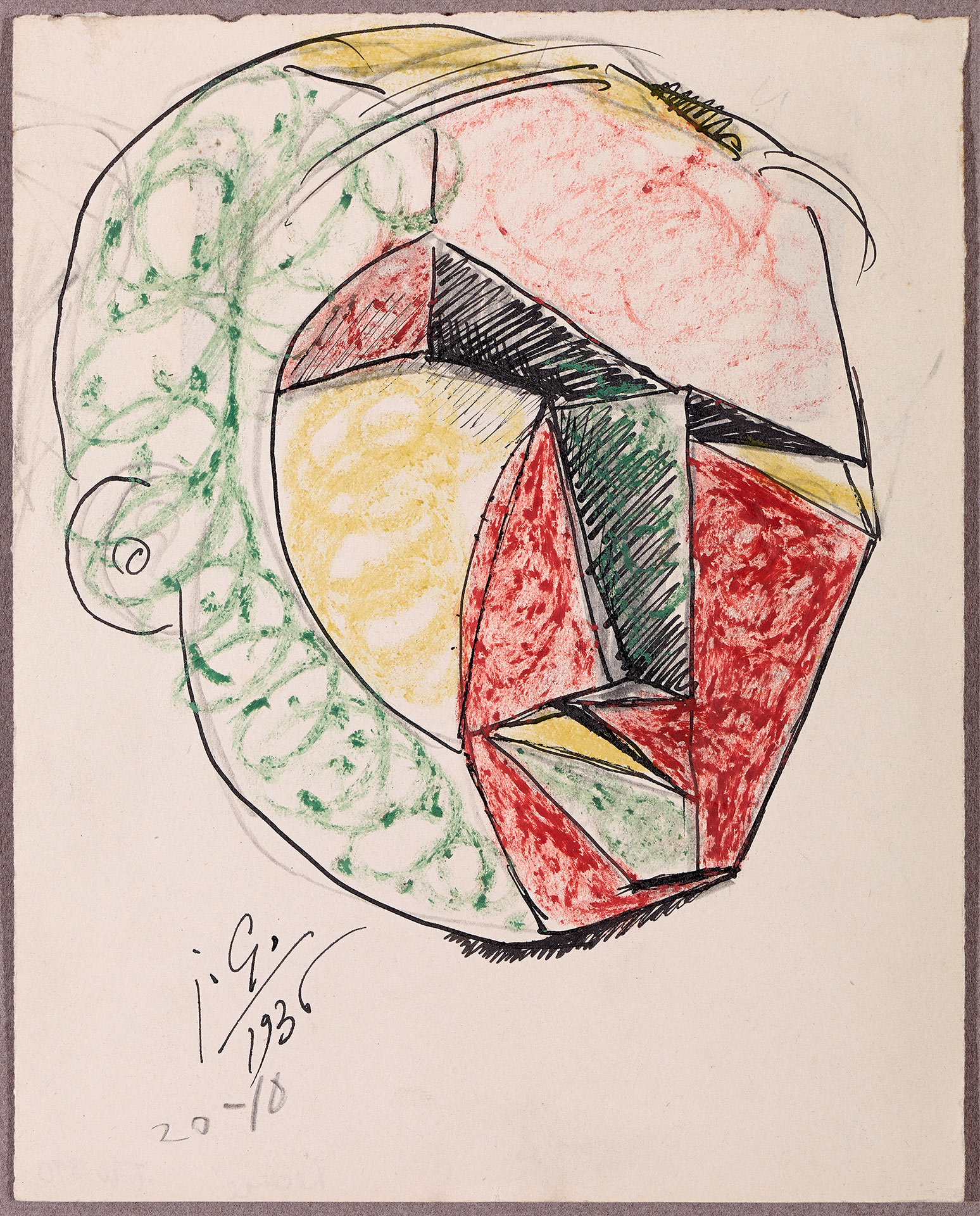

Julio González (Barcelona, 1876 – Arcueil, France, 1942)

Rigour Head

1936

WORK INFORMATION

Coloured pencil and Indian ink on paper, 21.5 × 17 cm

OTHER INFORMATION

Signed and dated in the lower left-hand corner: "J. G. 1936 / 2010"

Julio González is unanimously acknowledged as one of the most important names in modern sculpture. It has often been said that sometime around 1930, applying what he had learned as an industrial worker, González changed our understanding of sculpture by introducing a new material—iron or, more precisely, iron scrap metal—and a new technique—oxy-fuel or oxy-acetylene welding. With them he traded mass for empty space and volumes for planes and lines, paving the way for one of the most important trends in modern sculpture after that point: assemblage. González's new sculpture, rooted in his previous experience and triggered by his collaboration with Picasso, explored the construction of three-dimensional forms using lines, planes and voids, thus shattering the traditional divisions between sculpture, painting and drawing. He used a working method inspired by collage and even bricolage that also incorporated the sense of the "ready-made", conferring artistic status upon an object or even a fragment of an object. Those pieces therefore gave rise to a language that would synthesise some of the principal artistic concepts of his time, such as Cubism, Dada and Surrealism. Little wonder that, in 1956, the American sculptor David Smith hailed González as "the father of all modern iron sculpture".

However, González's mature work, relatively modest in terms of both format and quantity, contains quite diverse and even seemingly disparate proposals. In addition to pieces related to the use of iron and the demand for new working methods, González produced others that reveal his respect for traditional sculpture techniques. While iron assemblage allowed him to envision sculpture as the sum of formerly unconnected parts, his persistent use of carving confirmed him as a perhaps unexpected heir to Michelangelesque tradition and the notion of sculpture as a process of subtraction from a closed volume: the stone block. At the same time, González always made formal experimentation compatible with the desire to capture reality, particularly the human figure. This position, which might be interpreted as a survival of classical academic tradition in his work, can also be read as proof of his interest in all things human, expressed from the most varied perspectives: at times with a transcendent and even religious sense, and at others jocular or merely attuned to the ordinary and commonplace.

The piece in the Banco Santander Collection, a drawing entitled Tête Rigueur [Rigour Head], aptly illustrates the intersecting nature of González's art in all of the ways we have just mentioned: this is obviously the drawing of a sculptor, more interested in the study of volumes than in the anecdotal description of an individual's physical features. The reduction to a series of sharp planes reveals the late legacy of Cubism and the avant-garde vision of non-Western cultures. The curved lines of the hair recall González's delicate work as a goldsmith in Barcelona during the heyday of Catalan Modernism. In contrast, the general hardness of this face reveals his intense preoccupation with a key historical event: the Spanish Civil War, which he spent exiled in France. Indeed, in Rigour Head we can almost sense the silent echo of the contorted screaming women—occasionally identified with the iconic figure of the Catalan peasant woman, La Montserrat—in which González personified the resistance to fascism. [María Dolores Jiménez Blanco]