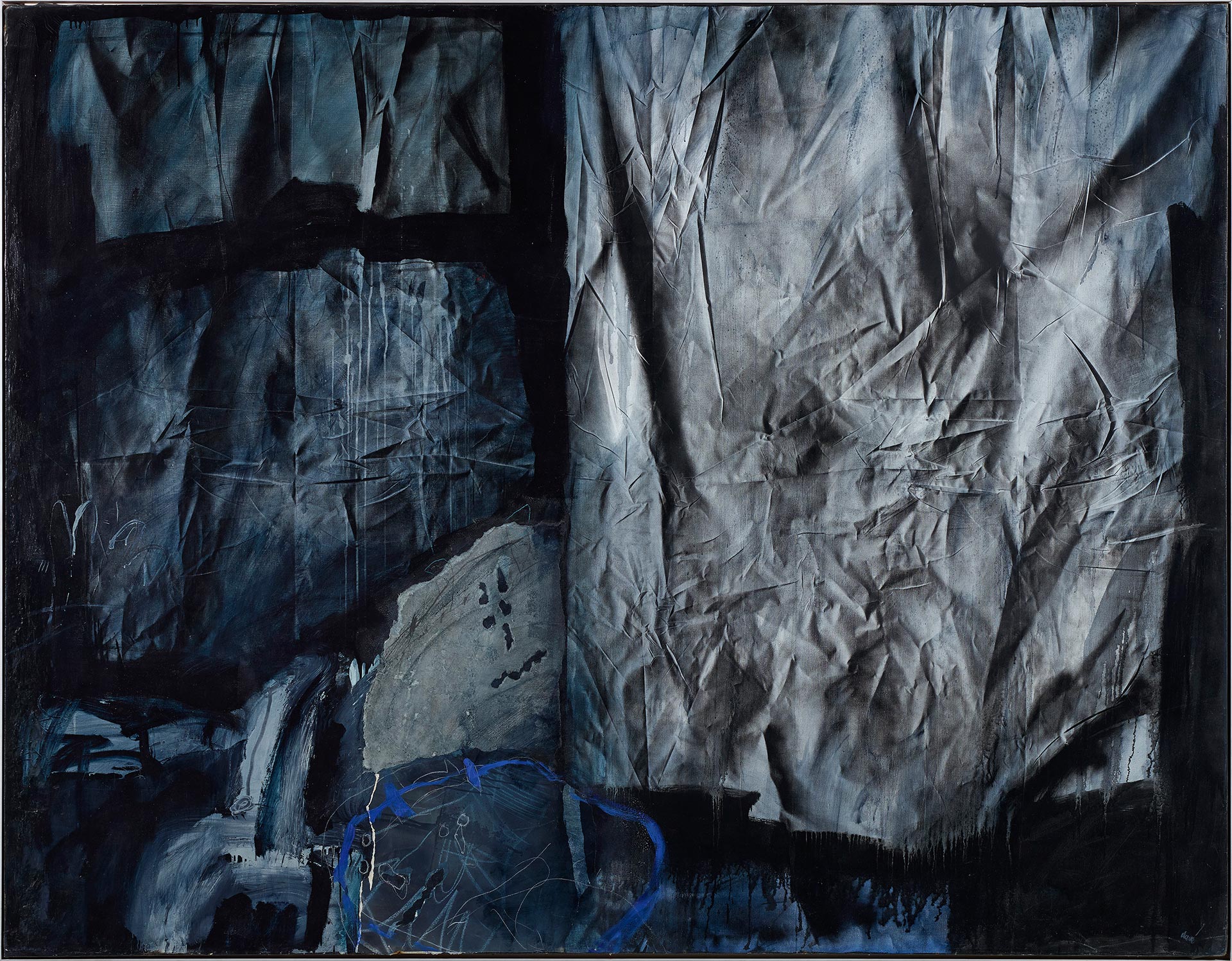

Antoni Clavé (Barcelona, 1913 – Saint-Tropez, Francia, 2005)

Fauns and Warrior (For Don Pablo)

1985

WORK INFORMATION

Oil and collage on canvas, 195 × 250 cm

OTHER INFORMATION

Signed in the lower right-hand corner: "Clavé" Inscription on the reverse: "Faunes et guerrier (A don Pablo)"

Antoni Clavé was part of the diverse group of Spanish artists who lived in the French capital before and during the Civil War, collectively known as the Paris School. Born into a humble family, in his youth he worked at a lingerie shop to make ends meet. He studied at the Sant Jordi School of Fine Arts and gained a foothold in the art world by applying his extraordinary talent as a draughtsman to film poster design and illustration. During the Spanish Civil War he fought for the Republic, and in 1939 he arrived in Perpignan with what was left of the Republican army. That same year he moved to Paris and created his first assemblages. After an early period of intimist work, in 1944 he met Picasso and his painting took off in a new direction that endured until well into the 1950s. This new orientation was obviously indebted to the master from Málaga, who decisively influenced his output: Clavé's canvases began to feature harlequins, musicians and painters in their studios. A clear example of this influence is La coupe [The Goblet], where the manner of composing the figures and even the goblet referenced in the title are strongly reminiscent of Picasso's work.

In the mid-1950s and throughout the 1960s, he worked on series of kings, queens and warriors that signalled his definitive transition to the figuration of Art Informel. These hieratic figures are characterised by bold colour contrasts and, in some cases, the use of assemblage. While his kings and queens are closer to traditional portraiture, the warriors series evinces a stronger spirit of renewal. In these compositions, the head and attributes are usually the most clearly defined part of the work, while the rest is a question of line, colour and matter. In Guerrier au fond rouge [Warrior on a Red Background], Clavé also employed a contrast typical of his particular palette: red and black, colours that link his work to Spanish pictorial tradition.

After that point, as we see in Peinture [Painting], the human figures in his compositions gradually lost their identifying features and were reduced to a jumble of lines; though he never abandoned figurative references altogether, these are clearly abstract works. Clavé's exploration of these two worlds was not devoid of ambiguity: in the case of Painting, colour and matter-rich density coexist with a cloth-covered table.

However, one thing remained constant throughout the artist's career: his interest in experimentation. His love of unconventional materials made collage his favourite medium of expression. As we see in the work Composición [Composition], the artist was forced to exercise restraint in the use of this technique. Following Picasso's advice not to overload or strain his works, Clavé had to concentrate on the essential: let the materials do the talking and strike the perfect balance between assemblage and painting.

After the 1960s, wrinkled fabrics would become a constant feature in his oeuvre. Despite appearances, they are not bits of cloth or paper stuck to the canvas but textures drawn with the painstaking accuracy of a precisionist painter. These trompes l'oeil became the focal point of a series of compositions in the 1980s, to which the painter added characters, schematic warriors and fauns with very few identifying features, as in Faunes et guerrier (A don Pablo) [Fauns and Warrior (For Don Pablo)]. For Clavé, this was a time of distancing himself from Picasso while also paying tribute to the master, of looking back at the long road travelled since the first Picassian influences of the 1940s. [Inés Vallejo]