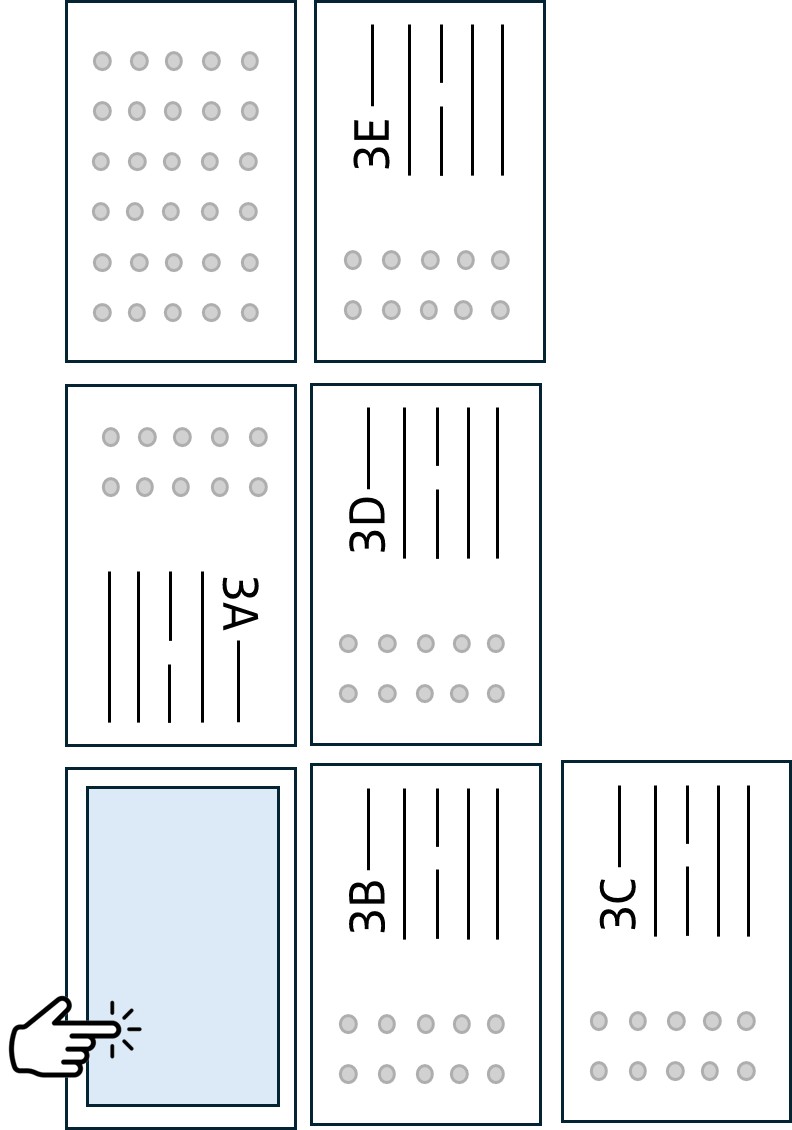

3A. Bank of Santander

Following the signing of the founding deed of the Bank of Santander on 3 March 1856, and in accordance with the Law on Banks of Issue of 28 January 1856, the circulation of its own banknotes was one of the Bank’s main lines of business. The issuance of banknotes served a dual purpose. On the one hand, it was a way of securing resources at no financial cost, and on the other, it provided a means of payment for trade, thus avoiding the costly movement of metallic currency.

The Bank commissioned a renowned London artist to design its banknotes. The obverse features – with some modifications – the symbols of the city of Santander: the fleet ship that liberated Seville in 1298; the broken chains; and the Torre del Oro (Tower of Gold). Other elements are also depicted: the cannons of the royal foundries of Liérganes and La Cavada; the flags from the coat of arms of the Royal Consulate of Commerce of Santander, founded in 1785; and the bales, barrels, and goods that represented the foundations of the city’s commercial wealth. The Bank kept its banknotes in circulation until 1874, when the Bank of Spain was granted a monopoly on the issuance of banknotes.

Beginning of the Bank of Spain’s monopoly

The 100 peseta note of 1874 was the largest denomination in the Bank of Spain's first official issue, after acquiring the exclusive right to issue banknotes. It featured Juan de Herrera, a leading architect of the Spanish Renaissance and a key figure in the reign of Philip II. Herrera was the architect of San Lorenzo de El Escorial—depicted on the banknote—and of the Royal Palace of Aranjuez and, possibly, of the layout of the Royal Mint of Segovia, a ground-breaking facility.

The theme for the first series of 1874 was great Spanish artists, paying homage to figures such as Rafael Esteve (engraver), Francisco de Goya (painter), Alonso Cano (sculptor) and Herrera himself. Each banknote featured a different thematic motif depending on its denomination, making it easier to identify, and promulgating Spain's cultural heritage.

With regard to security measures, the banknote introduced what was then an innovation: the tarlatan, a textile mesh embedded in the paper, that became a constant feature of 19th century banknotes. It also had a characteristic side cut, similar to that of a chequebook, which justified its issuance as an accounting document.

3C. Illustrious personalities

After commissioning the American Bank Note Company to issue banknotes on 1 January 1884, the Bank of Spain made a second issue that same year, dated 1 July, using its own means.

The theme for this series was Spanish politicians. The 1,000 peseta note features the Marqués de la Ensenada, who was a State Councillor during the reigns of Philip V, Ferdinand VI and Charles III, was distinguished in various fields and promoted important reforms. Among his achievements were the liberalisation of trade with the Indies, tax system reform and the creation of the giro real for international transactions, a key source of revenue that may have inspired the creation of Banco Nacional de San Carlos.

In 1884, construction began on the new headquarters of the Bank of Spain on Calle Alcalá and Plaza de Cibeles. The first stone was laid on 4 July, in a ceremony presided over by King Alfonso XII, the Queen and the Infantas. The architects commissioned to carry out the project received an annual salary of 6,000 pesetas, the equivalent of six banknotes like this one.

3D. The new style

The 50 peseta banknote issued on 30 November 1902 signalled a major revival in banknote design and production in Spain, which was to shape the rest of the series of the 20th century. Leaving behind earlier, 19th century style, it heralded the end of the side matrices or plates and tarlatan (a cloth mesh used as a security measure), opting instead for a more modern, rectangular and functional format, with white margins. To enhance security, a German machine was used to groove the paper, achieving a distinctive finish, although this had the disadvantage that the notes deteriorated rapidly.

The motif of the banknote pays tribute to the painter Diego Velázquez, whose portrait appears on the obverse. The reverse shows the work, Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan. The design and engraving was the work of Bartolomé Maura, an outstanding engraver who had won the first-class medal at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1901. This banknote ushered in a style that was to define the issues of the 20th century, with higher artistic quality and better technical measures.

The last banknote produced by the Bank of Spain

This was the last banknote to be produced entirely by the Bank of Spain’s workshops, which since 1874 had the exclusive right of issue. Despite having this responsibility, the Bank was unable to develop an adequate technical infrastructure to tackle the growing demand for banknotes, especially during the First World War, when money supply—mostly in banknotes—doubled to 6.9 billion pesetas. This lack of capacity made it necessary to turn to private manufacturers, both Spanish and foreign, to produce banknotes.

This specimen stands out for its beauty and symbolism. It was designed by Enrique Vaquer, an artist regularly commissioned for banknotes. The obverse depicts Mercury holding a spinning world in a clear allegorical reference to the necessity and well-being generated by trade. Indeed, the left rim shows the pillars of productive activities: Industry, Agriculture, Commerce and Navigation. The reverse depicts Hispania seated on a throne between the two pillars with a lion at her feet, decorated with various Spanish heraldic details. There is a watermark in the white reserved area of the paper, and it is possible to make out the profile of Charles I.

3E. F.N.M.T. - R.C.M.

After the Civil War and at the height of the Second World War, the Bank of Spain needed a stable and secure way to produce banknotes, as until then it had often depended on foreign producers. This changed in March 1940, when the Bank turned to the Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre (FNMT), with which it arranged the issue of 21 October of that year.

The FNMT, created in 1893 from the merging of the Mint and the Stamp Factory, had been modernised in 1923 when it became an independent body reporting to the Treasury. Its first headquarters, in what is now Plaza de Colón (Jardines del Descubrimiento), was demolished in 1970 and it was moved to its current location in Calle Doctor Esquerdo. From 1940 onwards, the FNMT took over banknote production once and for all by decree, and the Bank of Spain was obliged to use it as its sole supplier. That became the norm until the advent of the euro.

The 500 peseta banknote of this issue was the work of the engraver Sánchez Toda, who made a beautiful illustration of the Burial of the Count of Orgaz on the obverse and a view of Toledo on the reverse. It was issued in 1947, on English paper with embedded security fibres.